SAS Operation Nimrod, 45th Anniversary

On April 30th, 1980, six armed Arabistani/Iranian terrorists took over the Iranian Embassy in London. They took twenty-six hostages including one British Police officer, three British journalists and all the Embassy staff.

After six days of negotiations during which five hostages were released, a hostage was executed and his body thrown from the front door of the building. Less than an hour later B Squadron of 22 Special Air Service Regiment, the ‘Pagoda’ team, launched operation Nimrod. In seven minutes, the soldiers cleared the building in a dramatic rescue captured live on television.

One hostage was murdered as the assault commenced, but the remaining nineteen were rescued. Five terrorists were killed, and one was captured. For twenty-two years none of the rescuers spoke about the mission until John McAleese, Tom Macdonald and (author) Robin Horsfall took part in the BAFTA winning documentary SAS Embassy Siege by Louise Norman and Peter Taylor. Robin is the only survivor from that 2003 documentary. Following is a video summary by Robin and a detailed 10,000 word account of his part in the mission from his autobiography Fighting Scared.

break line

Pagoda

(Fighting Scared 2002., Robin Horsfall)

There was no leave when we got home from Ireland. We were going to spend most of our time in Hereford from now on and go home every night, so who needed leave?

Team training started almost immediately, run by the squadron handing over to us, G Squadron. This was always the case because counter-terrorist equipment was constantly being improved and even if men had done the job before, it was likely that drills and equipment had changed dramatically in the short time between tours.

The squadron was broken into two teams: 6 and 7 Troops were the red team, 8 and 9 Troops the blue team, and each team was further divided into two, assault and sniper. Although everyone was trained as an assault team member, only half were trained as snipers as well.

I had always loved shooting at long range and offered myself as a sniper. I talked up my time on team competitions and all the shoots I had done at Bisley, the Army small arms ranges near Pirbright. After a considerable amount of waffle, I got the job and the nickname Bisley Bob, later shortened to just plain Bisley.

The next four weeks were spent practicing assaults on buildings, buses, ships, and aircraft. I spent long days and nights firing my three sniper rifles at stationary and moving targets. My L49 was the standard British Army sniper rifle, accurate up to a thousand yards in the right hands. The other two were Tikka Finlander hunting rifles, one with a day-scope and the other with a night-scope. These were good only up to three hundred yards. The L49 fired a 7.62mm NATO ball-round, which was standard-issue ammunition. It had great range and could penetrate thick glass, wood, and brick. The Tikka fired 5.56mm hollow point. Hollow point was the best anti-terrorist ammo: when a round hit a man's head, it flattened itself, releasing all its energy into the point of impact. This created a massive entry wound but no exit wound- the bullet never came out. Fired at the skull, it had almost a hundred per cent kill rate, and the zero penetration of the hollow point prevented rounds going through terrorists and hitting hostages behind. It also stopped a wounded man from pulling the trigger as he died (with his head turned inside out, a terrorist hit with a hollow point died, full stop).

In April we officially took over from G Squadron and became the Pagoda team, the code word for the counter-terrorist team. We settled into a weekly routine in the killing house, a series of indoor ranges with ricochet-proof walls. Here we would practice with our MP-5 Heckler and Koch submachineguns (SMGs) and our 9mm Browning pistols. Four hundred rounds per man per day was not unusual.

The MP-5 is the best SMG in the world. It fires from a locked-bolt position, using a delayed blow-back action, which reduces the recoil and weight transfer as the weapon fires. Loaded with a thirty-round magazine, it weighs only 6.5 pounds. With training, a man can fire a three-round burst into a four-inch circle at five yards without aiming through the sights.

One drill was to burst into a room where a live hostage was sitting in a chair. He would be surrounded by targets, each with a four-inch circle on its face. As we entered the room, we would fire a short burst at each target and rescue the hostage. The team leader would not be happy unless all the fired rounds were inside the circles.

The sniper team spent full days on the ranges, using all our sniper weapons. When we arrived, we would fire one round from each combat ready weapon. If we had to shoot someone for real the following day, the first shot was the only one that would count. We would then spend the day firing at different ranges and at targets moving at different speeds. With practice, we could group our shots into a one-inch-diameter circle at one hundred yards and hit a man in the head at two hundred yards when he was running. If he was standing still, we could hit him somewhere in the body at six hundred yards. Hitting a target is not just a case of pointing a weapon and pulling the trigger, no matter what it looks like in the movies: the skills involved take endless hours of practice, and you're only ever as good as your last day's training.

At least once a week we would attack different types of targets using live hostages, CS gas and blank ammunition. We each took our tum at being a hostage, which wasn't any joke. CS gas in confined spaces is a real body blow; it's no fun coughing, weeping, and choking for ten or twenty minutes after being gassed.

Many of our weekends were devoted to training with the police. An exercise would begin with the team members at home. We all wore beepers, so we could be alerted by a series of numbers indicating an exercise call-out. Having arrived in camp, we would prepare the six white Range Rovers and six Transit vans that carried all our primary equipment and then drive as quickly as we could to the exercise area, which could be anywhere in the UK. We drove in convoy, the lead vehicle in constant contact with all the vehicles behind. When the opposite carriageway was traffic-free, the message on the radio would be 'Road clear', then all the following vehicles would overtake any intervening traffic. When a car appeared coming towards the lead vehicle, the message would be 'Traffic,’ and the followers would all pull over to the correct side of the road and wait for the clear signal again. Even with blue lights flashing and sirens blaring, it scared the hell out of ordinary drivers when they were overtaken by six Range Rovers round a blind bend.

Once at the incident site, the squadron commander would liaise with the police. When the situation was deemed to have broken down, we would attack the target and rescue the hostages. We got to try out various methods of entering and assaulting buildings, and different targets.

We would sleep with all our equipment, standing by day and night for any emergency. On Sunday we would go back to camp and clean and prepare everything for a call-out. Monday we would start all over again. All this became just routine.

Being in Hereford for a long period of time gave me a chance to develop my relationship with Heather. She was the best thing that had ever happened to me. She cared about everyone and saw right through my tough-guy exterior. If I was putting someone down for being weak or inadequate, she would remind me of my own weaknesses and then build me back up by telling me that not everyone could be like me -thank God for that small mercy. She never lied about anything important: her sense of honesty was profound. She wasn't timid, though: if she thought I was wrong, she told me so, and more often than not, especially where my behaviour was concerned, she was right.

Heather gave me everything she had, emotionally; she was soft, warm, and caring, and for the first time in my life someone loved me unquestioningly, and in return, I began to feel secure about myself. I relaxed and stopped viewing every other male on the planet as an aggressor. I became less aggressive myself to the world at large. If I went into a pub, I didn't glare at men who got too dose to me or insist on standing with my back to the wall. Being single had been a lonely experience that had involved going from one place to another and from one girlfriend to another. All that now changed: for the first time in six years, I had a home to go to and a beautiful woman there waiting for me.

We had nothing. I was still on private's pay; she was on income support. There was a three-piece suite, two beds, a cooker, and a table and three chairs. It took us two months to save up for curtains. 'The SAS comes first,' I told her. 'We'll never get married.' 'Yes,' she would say, 'but if we ever did...'

On Wednesday, 30 April l980, the Pagoda team was waiting to go to Scotland to take part in another exercise with the police. The vehicles were ready, and we were sitting around drinking tea in the blue team's waiting area. It was going to be a long drive to Edinburgh, and we wouldn't be back until Friday.

At 1120 hours, on BBC Radio, Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister, was heard to say, 'I almost lay awake at night thinking, what I would do if we had fifty hostages taken at our embassy?' She was referring to the continuing problems encountered by United States President Jimmy Carter in Tehran: all the American embassy staff had been taken hostage by members of an Islamic fundamentalist organization, supported by the new revolutionary government of Iran. A rescue mission had been mounted by the USA and had failed, resulting in the deaths of many American soldiers and the severe embarrassment of the US government.

As she spoke, just two miles away from BBC Broadcasting House three Arab terrorists were walking from their temporary headquarters at Lethem Gardens, Earl's Court, to the Iranian Embassy at 16 Princes Gate, one of London's most fashionable terraces. Police Constable Trevor Lock, a tall, well-built man, aged forty-one, was midway through his shift guarding the front door of the embassy. He was a long-serving member of the Diplomatic Protection Group (DPG), and was armed with a .38 Smith and Wesson police revolver that contained only six rounds of ammunition .Inside were Sim Harris, a long-haired, bespectacled BBC sound recordist, and Chris Cramer, a BBC TV news field producer, who were chasing up delayed visas for a future visit to Iran.

As DJ Jimmy Young played the 'The Other Side of Me' for the Prime Minister, the three young Arabs raced from a red car and fired several shots through the glass-fronted doors of the embassy building. Splinters of glass exploded into Trevor Lock's face, and before he could react, he was forced, bloody-faced and shocked, through the doors and into the building, an Uzi submachinegun thrust into his chest. In the entrance hall, the original three Arabs were joined by three more, who had been waiting on some pretext inside.

PC Lock and the BBC men were placed in a small upstairs room with embassy chauffeur Ron Morris. With their hands held above their heads, they watched and listened to the increasing commotion in the building. The gunmen were shouting for Ali Afrooz, who was Ayatollah Khomeini's charger d'affaire in London. They finally found him and threw him in with the British hostages. He had a nasty gash on his face and a black eye. The gunmen apologized constantly to the British prisoners, saying again and again that their problem was not with any non-Iranians.

Back in Hereford, as we were waiting to leave for Scotland, word of the takeover at the embassy came through. Big Bob smiled coldly. 'My Tikka is ready.' he said, closing one eye and squeezing an imaginary trigger. At about midday, Major Hector Gullen called us into the tearoom for a briefing. The exercise was off.

Now I saw Hector at his best, with something to get his teeth into. He breathed confidence and enthusiasm into the rest of us. By the time he had finished talking, I knew why he was in command of a squadron. We were to wait in Hereford to see how things developed. In the meantime, we could go home and grab anything we might need for a prolonged period away, like extra shaving kit or money.

I went back to Heather's flat and gathered some bits and pieces. She would be expecting me back in a couple of days, so I needed to let her know something about what was happening. Because she wasn't my wife, if anything went wrong the Army wouldn't contact her. I left a note on the mantelpiece telling her that I would be away for longer than I thought. If she needed any more information, she should watch the TV.

Back in camp, information started to come in via the television and radio. In cases like this, the media, with all their resources, can often find things out faster than the intelligence services. We double-checked all our equipment and waited, all of us secretly hoping beyond hope that this would really be it and that we would be called in. Such an incident had never happened before in the UK; the only previous com parable situation was London's Balcombe Street siege, and in that case, the IRA terrorists surrendered when they were told that the SAS were on the job. The Regiment had also assisted and advised at Mogadishu, in Ethiopia, when a Lufthansa jet had been hijacked, but our team had not actually been used in the operation.

By 1215 hours all traffic through Princes Gate had been diverted, a whole area, covering one square mile, had been cordoned off, and a growing army of press photographers and sightseers had begun to gather.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner John Dellow took charge of the police operation, backed up by Commander Peter Duffy, head of the Metropolitan Police Anti-Terrorist Unit. By 1700 hours, Deputy Assistant Commissioner Peter Neivens was telling reporters that he believed that there were as many as twenty people in the embassy, with three gunmen. In fact, there were twenty-five hostages and six gunmen.

Information was coming in every minute, with constant updates on the TV. The terrorists were anti-Khomeini, and more information about Trevor Lock and the other British hostages was becoming known. The gunmen were now demanding the release of political prisoners in Tehran.

We saw the British hostages as a bonus- they increased our chances of being sent in; if all the hostages had been Iranians on Iranian sovereign territory, the possibility of our involvement would have been remote.

By 1800 hours the military had still not received a request to become involved, but the head-shed (senior officers in HQ) decided that we should move the unit nearer to London. We drove out of Hereford in dribs and drabs, leaving town by different routes, with orders to get together in the cookhouse at Beaconsfield when we arrived. Tom, Mac, Nick, and I loaded ourselves into our white Transit and set off via Gloucester to the M40. We arrived at about 2300 hours and made our way to the rendezvous.

At about midnight we moved on to Regent's Park Barracks and got our heads down for the night. By now the siege was well under way. The terrorists were led by 'Salim', a slight man, about five foot six tall, with a goatee beard. He wore blue jeans and a green anorak. He was the only one of the six who could speak fluent English. The other terrorists went by the names of Faisal, Abbas, Shai, Makki, and Ali. All were heavily armed, with automatic weapons, handguns, and grenades. They said they were members of the Arabistan People's Political Organization. Their initial demands were for the release of ninety -one political prisoners, members of their movement. They also wanted to highlight the plight of the four and a half million Arabs who were suffering under the regime of Ayatollah Khomeini.

At the embassy, Ali Afrooz and an Arab journalist named Mustapha were given a two-and-a-half-page statement that the terrorists wanted broadcast to the world. They were told to telephone several media groups to make the announcement, but the calls were interrupted by the police, and they had to hang up.

Since the hostages had been taken, one, a pregnant woman, had become ill. She was vomiting and complaining of stomach pains. Salim was asked to provide her with a doctor. The police refused to allow any other hostages to be taken, so Salim allowed the woman to be released.

By Thursday morning the situation was developing rapidly. The Home Secretary, William Whitelaw, had given authority for the SAS to deploy closer to the target. The police, meanwhile, had established phone contact with the terrorists, and negotiations for the release of the hostages were underway.

By 1015 hours, Chris Cramer was writhing on the floor in agony, holding his stomach and sweating profusely. He had become very ill during the night and was getting worse. Sim Harris spoke to the police negotiators on the telephone and asked for a doctor. The police offered drugs, claiming, 'To get a doctor to enter the building would require permission from a higher authority.' Cramer was carried to the ground floor and laid on an old mattress by the police telephone. 'Get me a doctor, I can't stand the pain,' he cried down the line. The police told him they could not find a doctor who was prepared to enter the building, so Harris persuaded Salim to release the sick man. He agreed, reluctantly, and this was a great success for the authorities. They had established that the terrorists were prepared to negotiate the release of some of their hostages if the situation was appropriate. Every individual released was a step towards a successful conclusion. Salim, feeling that he was losing ground, now upped the stakes. He demanded a plane to fly to the Middle East by midday. He warned that the building was booby-trapped and claimed that he could blow it up at a moment's notice. The police negotiators told him that the midday deadline could not be met, so it was extended for two hours. The terrorists, undecided as to what to do next, allowed the two o'clock deadline to pass without further demands.

At 2000 hours, Trevor Lock appeared at a window on the second floor. He told the negotiator that the terrorists were going to kill people if their demands were not met. Unbeknown to anyone, Lock was still in possession of his .38 pistol, which was in its holster under his overcoat.

At 0100 hours the whole squadron moved into the Royal College of Surgeons, two doors away from the embassy. We parked a large pantechnicon truck at the end of the block and passed all our equipment over the wall. This took a considerable amount of time. The gear was then taken around the back of the building and in through the rear doors. The police had already begun to use the second floor as an incident control centre. We took over the remaining available space, reorganized our kit and prepared for the Immediate Action (lA). This was the first assault plan, drawn up quickly as soon as the team was on the ground and ready to go. It allotted everyone a point of entry and an area of responsibility. If the terrorists started shooting, at least there was a plan, albeit a worst-case scenario- obviously, the more time we had to prepare, the better. My role would be to pump gas in through the windows as the assault team went in and then be prepared to follow them in as support. If the assault went well, I would then be responsible for handling the prisoners.

I got out of my blue jeans and sweatshirt and started to kit up. First, I put my gas suit on over my underwear and T-shirt, then, on top of this, I wore a set of plain black overalls. Over the overalls I wore my body Armor, which had a ceramic insert in the front to stop high-velocity bullets. The next layer was a black suede utility vest, with pouches for stun-grenades and a knife attached by a quick-release fastening for cutting myself free of entanglements. Around my waist I wore a thick leather belt with a leather pouch divided into three narrow compartments, each containing a thirty-round magazine for my MP-5. Strapped to my right thigh was a quick-release holster containing my 9mm Browning pistol with an extended twenty-round magazine.

I picked up my MP-5 and placed the sling attached to it across my back. The sling was clipped at the front and held the weapon tightly across my chest. In this way I could move through restricted entry points and, with one thrust of my left hand, release the clip and bring the weapon into the firing position to engage the enemy. All this equipment weighed more than thirty pounds. I was carrying one hundred and forty rounds of ammunition and two stun grenades. As a small comfort, a shell dressing for treating gunshot wounds was strapped to my right shoulder.

Despite what was claimed in the otherwise generally accurate media coverage, we didn't wear balaclavas; our faces were covered by standard NATO issue SR-6 gas masks, with the hoods of our dark green gas suits pulled over our heads and sealed tightly to prevent gas penetrating to our skin.

Our team's intelligence section was led by 'Belt Kit Joe'. While we were preparing ourselves, he was setting up an intelligence centre on the second floor. The police hadn't been able to become organised in this department, probably because there were so many different units involved: each different police group had its own rank structures; senior officers had no central authority and didn't know how to deal with a situation of this magnitude. Because Joe was military, it set him apart from these internal politics, and all the police units began to bring their information directly to him. By the time of the first briefing, he had already put together a very good plan of the embassy.

The Iranian embassy contained fifty-four rooms. Many of the internal doors were security doors, and some of the windows were made of armoured glass. At that moment Joe didn't know what was where, but the caretaker had been located, and more information would be available soon. Media photographs had been enlarged and placed on a large board in the operations centre. We spent a lot of time studying them to be able to separate the bad from the good if we went in. Clothing was as important as faces in terms of recognition. One mistake and I could find myself shooting a hostage or get shot myself as a result of hesitating.

We quickly settled into the routine that we had practiced over and over again on exercises. Red team stood by in their kit while blue team rested in their overalls. After eight hours we would swap over. We had brought in camp-beds, but Captain Juster had found himself a comfortable bed upstairs. A cartoon soon appeared on the wall depicting him with a crown on his head, ordering more steak and champagne for breakfast. All we could do now was wait - the hardest part of all. To relieve the boredom, practical jokes and adolescent gags became the order of the day. Wacky Races, the popular children's cartoon of the time, had a squad of gangsters, the Ant Hill Mob, constantly trying to rescue Penelope, the damsel in distress. Each of our teams began referring to the other as the Ant Hill Mob, or the Ants for short, and there were frequent cries of 'We'll save you, Penelope'. Our language was full of security-speak that was unintelligible to anyone else: I'll meet you at the obvious, with you know who at the obvious time.' The police were bewildered by our behaviour and found it difficult to converse sensibly with any of us.

By the end of the day the caretaker had been exhaustively questioned, and blueprints of the building had arrived. When it was discovered how many of the doors and windows were reinforced, it became clear that if an assault had gone in early, several of us would have been killed.

Early Friday morning, workers began digging up the road close to Princes Gate. The noise provided camouflage for the Secret Intelligence Service, who were hand-drilling holes in the walls of the building to insert a few listening devices to help gather information.

At 0900 hours, Trevor Lock and two other hostages, Mustapha Karkouti and Dr Ezati, the Iranian press attaché, appeared at that same second-floor window. A gun was being held to the back of Ezati's head by Salim, who shouted that he intended to kill a hostage if his demands were not met. Ezati collapsed, foaming at the mouth.

At 1100 hours, one of the women hostages told Salim that she had heard noises in the wall. Salim became very agitated and asked for reassurances from the police that nothing untoward was happening. The police assured him that while there were hostages in the building, they would not risk their welfare by doing anything stupid.

Meanwhile, a mock-up of the layout of all five floors of the embassy had been erected at Regent's Park Barracks. It was constructed from hessian and timber and was extremely fragile. We were taken, half the team at a time, to view the mock-up, so that we could familiarize our selves with the layout of the building. Unfortunately, at this stage we did not know what our specific tasks would be in the event of an assault, which meant that we had to try to familiarize ourselves with the whole building, an almost impossible challenge. I returned to the Royal College of Surgeons none the wiser.

Our plans were being updated regularly. The IA was now becoming a full-scale assault plan, with several different options. The terrorists had earlier asked for an aircraft, so we had to make various plans in case they were allowed to leave the building and travel to an airport. Obviously, at any point the situation might change, and we could be called to act. We had to be prepared for every contingency: the one thing we didn't want to have to do was to improvise a rescue mission for which we had not planned or rehearsed. Proper planning prevents piss poor performance...

The deteriorating situation in the embassy caused us to stand to, ready for immediate action, several times. If Salim or one of the other terrorists decided that enough was enough and started killing the hostages, we would be ready to go in at a moment's notice. It was a credit to the negotiator that he always managed to keep the situation calm.

Meanwhile, in the college, we continued to apply our own methods of dealing with the tension: cornflakes in sleeping bags, salt in tea, and water pistol ambushes at high noon. This did nothing to instil confidence in our police colleagues; in fact, they were beginning to view many of us as complete buffoons who took nothing seriously. We would take it seriously all right when the time came, but we were not going to sit around all day sharpening knifes and glaring angrily at each other, like something out of a Rambo movie. We spent most of our time watching the world snooker championships on TV.

Before we could launch any attack, the police would have to officially hand over control to the military. Ina sudden emergency this could be done by the senior police officer on the ground, but if we were carrying out a planned assault, permission would be requested by the Police Commissioner from the Home Secretary, William Whitelaw, who would, in turn, refer the request to the Prime Minister.

The siege was now two and a half days old, and the terrorists had failed to achieve any of their aims. They wanted a platform from which to tell their story to the world, and their failure to acquire that platform was increasing the tension. They were becoming tired as the days wore on. They were also becoming familiar with the hostages, which would make it harder to execute them without provocation. Something had to give.

They now asked for three Arab ambassadors as negotiators and reiterated their demand for a plane to the Middle East for themselves and the hostages. They promised to leave the non -Iranians at the airport. The negotiators stalled for more time. The longer they could delay any decision, the more chance there was of a surrender. As the third day ended, a female hostage again reported noises from the wall. Sim Harris asked Mr Naghizadeh, the second secretary, to order the women to keep quiet about the noises, but they took no notice and continued to try to ingratiate themselves with their captors.

The mood was changing, and we could sense it. We were now forbidden to leave the building. As it became dark, we stood to, ready once more to go in. Inside the embassy an argument was taking place between two terrorists. My heart pounded in anticipation. I stood by the back door, ready to go, but the storm subsided, and we could breathe easily again.

AT 1147 hours on the Saturday, Ali Afrooz pleaded with the police to take the terrorists' threats to kill someone seriously. Trevor Lock then read out a prepared statement, in which he stated that the police's delaying tactics were causing great tension.

At 1530 hours, BBC boss Tony Crabb spoke with Sim Harris about broadcasting the terrorists' statement to the world. Harris was visibly frightened, and impatient with the lack of co-operation from the authorities. Didn't they realize his life was in danger? Salim, who was holding a gun on Harris, became visibly angry, so Tony Crabb agreed to make a broadcast as soon as possible. Salim relaxed, so Crabb asked whether he was prepared to make a goodwill gesture by releasing some hostages. Salim said he would.

By 1900 hours there was still nothing broadcast on the radio, so Salim sent Trevor Lock and Mustapha to the window to ask why. The police said that they would only allow the transmission to go ahead once two hostages had been released, and not before. On hearing this Salim lost his temper and declared that he was going to kill a hostage, but Mustapha managed to calm him down and persuaded him to release one of the captives, pointing out that if this got him his broadcast then that would be a considerable achievement. Mrs. Haydeh Kanji, another pregnant hostage, was released.

Subsequently it became clear that Salim was truly at the end of his tether, and not in the mood for further compromise. 'Either there is a broadcast, or a hostage will be shot,' he proclaimed. He added, however, that he was still prepared to release another hostage if the broadcast was made. The police confirmed that the broadcast would be made at 2100 hours.

At the appointed time a statement was read out word for word on the BBC World Service, and Salim, true to his word, released another hostage. For the moment, the tension had eased.

Inside the college, however, tension was increasing. Soldiers who had never worn their ceramic plates during training started to insert them in their flak jackets. Some of these jackets had flaps that covered the lower waist. These had always been unpopular, as they were heavy, but now they were becoming as hard to find as rocking horse shit.

As night fell, the whole squadron was assembled in the ops room for orders. Hector briefed us on a full-scale assault on the building. As there were so many rooms in the embassy, the whole squadron would act as one assault team. Support would come from extra troops brought in from Hereford. As many access points as possible would be breached simultaneously, every floor would be hit at the same time. Entry points would be blown with special explosive charges, designed to remove windows and doors without killing anyone standing behind them. One team would move across the roof and lower a set of charges down into a chimney-like hollow in the centre of the building. At a given signal they would explode the charges, descend a small stairway from the roof and take out the top floor. Another team would abseil from the roof to the second floor, blow in the windows at the rear and take out this area. At the front of the building, a third team would jump across from the neighbouring first-floor balcony and enter the main hostage holding area. Team four was to blow the double doors at the rear on the ground floor and hold the stairs. (I was in team four.) Team five would take out the basement after also entering through the back door. Two men were to remain outside to control prisoners. This was the reception party. The extra dozen or so troops that had come up from Hereford would take the sniper rifles and offer cover from the surrounding buildings.

On Sunday, as we sat watching the Benson and Hedges snooker championships on TV, the police negotiations were going well. Aside from the broadcast, no concessions had been made to the terrorists, while hostages had been recovered, and information had been gathered that would make any assault more likely to succeed.

Inside the embassy, however, nerves were beginning to fray to breaking point. Salim began writing anti-Khomeini slogans all over the walls. He knew that he was losing the psychological battle with the police and if he was going to make a stand, it would have to be soon. The alternative was to lose face in front of the world. He was torn between two options: to surrender, or to kill a hostage. First, he would scream and threaten, then he would calm down. He asked Sim Harris whether he thought he had gone about things in the right way. Harris told him that although most of the Western world sympathized with his cause, they would not tolerate the murder of hostages. If he killed someone, he could not hope to win.

Afrooz and one of the embassy workers, Lavasani, took great offence at Salim's insults to their highest religious leader. Lavasani lunged at one of the gunmen and was promptly wrestled to the ground. A weapon was cocked and held to his head. For a moment it looked like the man was going to die, but Trevor Lock intervened and bawled Lavasani out in front of everyone.

We were aware of the noise and confusion, and once again we stood ready to go. Our tasks hadn't changed, but in the event of an IA we in team four would now go in without using explosives, which were all deployed elsewhere. Sledgehammers would have to do the job instead. I knew that before we could go in there would be a hiatus while we took official control. I also knew that until someone was killed, it was unlikely that the attack would be authorized. I stood calmly at my position by the rear door of the college. My gas mask was pulled back and I was drinking a cup of tea. Now the police had no idea what to make of us: we had been buffoons before; but here we were, waiting to go into the building, calmly drinking tea and talking about missing the snooker on TV. I suppose they thought we were strange, but as far as I was concerned, all this had been going on for some time now and there was no point in getting excited until something was about to happen.

In the embassy things began to calm down again, but Lavasani had now become isolated from the group as someone the gunmen could hold a grudge against. It appeared as if he wanted to be a martyr: he had told Harris that he was single, with no responsibilities, and per haps he had deliberately set himself up as the victim should Salim decide to kill someone. Before the incident with Lavasani, the negotiators had believed they were winning; now the chances of the situation breaking down had increased, so top military lawyers were brought in to brief us on the legal situation in the event of an assault taking place. We were still subject to the full weight of the British legal system: any action we took had to be justifiable in the eyes of the law. It was very similar to the situation in Northern Ireland. We couldn't just kill the terrorists: we had to take them prisoner unless we believed that our lives, or other people's lives, were in immediate danger. The law stated that we should rescue the hostages and, if necessary, kill the terrorists; in our hearts, we wanted to kill the terrorists and then save the hostages. What was important was that we knew what to say if something went wrong.

It is rarely what a man does, but what he says which convicts him of an offence. We were being protected from the possibility of someone, from the safety of his easy chair, later judging us for our behaviour in the face of an enemy who had been trying to kill us. We knew that if we attacked, we would win. We were committed to our task, and we outnumbered the enemy ten to one. Who would die was the only question remaining. I just hoped it wasn't going to be me.

At 1110 hours on Monday, 5 May, Trevor Lock told the police that Salim would kill a hostage at 1140 if his demands were not met. Ten minutes later he asked for the negotiators. He wanted them quickly.

The 1140 deadline passed without incident. At 1215 Lock told the negotiators over the phone that Lavasani was being tied up. Salim picked up the phone and calmly told the police that they had had enough time.

Within seconds three shots rang out. Salim came back on the phone and said, 'I will kill one now and another in forty-five minutes. The next time the telephone rings it should be to tell me that the ambassadors are coming. I do not want any more messages.'

At 1315 Trevor Lock informed the police that the gunmen had shot one hostage and that they would shoot another in thirty minutes. There was still some doubt as to whether someone had been shot or not. Was it a bluff? No one knew. Once again, the deadline passed. It was down to a face-off. Either Salim shot someone, or he surrendered. Salim knew that they were calling his bluff.

Police Commissioner David McNee sent a letter to Salim. It said:

“I think that it is right that I should explain to you clearly and in writing the way in which my police officers are dealing with the taking of hostages in the Iranian Embassy. I and my officers deeply wish to work to a peaceful solution of what has occurred. We fully understand how both the hostages and those that hold them feel, threatened and frightened. You are cut off from your families and friends. But you need not feel threatened or frightened by the police. It is not our way in Britain to resort to violence against those who are peaceful. You have nothing to fear from my officers provided you do not harm those in your care. I firmly hope that we can now bring this incident to a close peacefully and calmly.” Salim was not impressed!

We made our final preparations for the assault. Abseil ropes were fixed to the roof, explosives were prepared and moved close to the forming-up points, gas filters were checked, laces were tightened. Now it looked as though something might be happening; the police officers fell silent. They had done their best; now it was our turn.

As the siege approached its climax, we watched another battle reach its grand finale: Cliff Thorburn and Hurricane Higgins were slogging out the last few frames of the snooker final on TV. We were ready. There was nothing left to do but wait calmly for the order to go or to stand down.

In the Cabinet Office briefing room, the Prime Minister, the Home Secretary, the Police Commissioner and SAS Colonel Mike Rose were trying to come to a final decision as to whether to hand over control to the military and stage an assault on the embassy. Margaret Thatcher said that if the terrorists killed another hostage, the assault should go ahead. Shots had been fired; all we needed now was a body.

At 1913 hours four shots exploded from the interior of the embassy and a few seconds later Lavasani's body was thrown onto the front steps, in full view of the world's media. Five minutes later Lavasani was confirmed dead, and Margaret Thatcher gave the order to hand over control to the military. The assault was on.

I crept quietly out of the back door of the college and across the concrete patio towards the rear of the embassy. I looked ahead of me at Robert as he began to insert detonators into the explosives and place them on the back door, then I looked up. Above me, four men began to descend slowly from the roof on their abseil ropes. Behind me Big Bob was wielding an eight-pound sledgehammer as a back-up should it be needed to get through the door.

I gripped my MP-5 in both hands and thumbed the safety catch, assuring myself once again that it was off. The only sounds I could hear were the static hissing in my earpiece and the sound of my heart pounding in my ears. My greatest fear now was of making a mistake that might endanger a life- especially mine. My mind raced. Watch the windows, Robin. What do I do if someone looks out now? Don't rush. Is my pistol still in my holster? Where is my partner?

The police dogs, which were being held back just inside the doors of the college, began to feel the tension in their handlers and started barking and howling. Why don't you shut the bastard dogs up, I thought. The fear that had for so long been my greatest enemy welled up inside me like a balloon, waiting to escape from my throat. Hello, I thought. I'm glad you're here. Without you I wouldn't be functioning at my best. I need to be scared to be alert.

The smallest sounds were magnified, and time seemed to slow down.

Around me team members moved into position calmly and without undue haste. Only seven years earlier I had been a frightened young man on the brink of adventure, bullied and scared. Now I was walking forward into a firefight, the fear under control, my commitment to the task complete, in the knowledge I was ready, that I was the best man for the job.

Knowledge and training had dispelled my fear. I was in control. The sound of breaking glass made me look up. One of the descending abseilers had put his foot through the window. Ahead of me Robert struggled to finish preparing the explosives that would remove the door from its hinges. Hector had to make a decision, and fast. Had we been compromised early?

Salim was on the phone, talking to the negotiators, as the glass broke. 'I heard something, something is happening!' he shouted.

'Don't worry, it's OK: he was told by the man at the other end of the line. 'There's no problem, nothing to worry about.'

'Yes, there is, there is a noise!' Salim shouted.

Hector could hear the conversation as it took place. He took the microphone from the hands of his signaller and said, 'GO, GO, GO!' Now we had to improvise - only half the men were in their start positions. Boom! The explosives in the central chimney exploded. The team ran down the stairs and into the top floor as glass, debris and smoke shrouded them in a cloak of invisibility. The abseilers, already down on the rear balcony, broke the windows and threw stun-grenades into the room before following them in. At the front, two men leapt over the balcony and placed their own charge. Before they could move back it was fired, removing the window. In they went, just in time to see one of the terrorists raising his gun to a hostage's head. Two bursts and the gunman were dead.

In front of me Robert was trying to get the wires into the firing device to remove the back doors. 'Never mind ‘that; shouted Big Bob. He ran forward with the sledgehammer and mashed the door to pulp. His partner launched two stun-grenades and in they went.

I looked up as three bullet holes appeared in the window above my head. Dangling on his rope about twelve feet above the balcony and twenty feet from the ground was one of the assault team. He was stuck; his rope jammed in the figure-of-eight abseil device attached to his harness. The curtains beneath him had been set on fire by the grenades that had exploded when the first group had entered. The flames were climbing higher and higher and were now lapping against his legs. His screams of pain sounded over the radio.

I saw two of the team on the roof attempting to cut him down, but it was a difficult task as he was now kicking himself away from the wall to get free of the fire. The rope would have to be cut so that it parted on the in-swing, and he fell onto the balcony and not onto the solid concrete steps further down. I watched him dangle in the flames and considered what, if anything, I could do to save him. I felt helpless, but, realizing that I was not going to be able to do anything useful I took my place by the rear door and got on with my job.

I was a reserve, ready to respond in any area where help was needed. My partner, 'Ginge' from 8 Troop, was standing opposite me, staring into the gas and smoke-filled room. As the sound of gunfire swelled into an almost continuous crescendo, I saw a man stumbling around at the bottom of the stairs. He was wearing a large black over coat. His fair hair identified him to me immediately. 'Over here, Trevor!' I shouted. He turned and stumbled towards me, and I took his arm and led him to one of the reception parties on the back door. PC Trevor Lock had been our priority. He was one of us, one of the team. He had to come out alive, and the guys upstairs had indeed got him out first. As I returned to my position just inside the door, I could hear Hector shouting down the radio for information, but everyone was too busy to respond. In front of me a chain was beginning to form on the stairs: everything was going to plan. 'Reserves go in now!' Hector shouted on the radio. Ginge launched himself forward into the building, with me following behind. As we entered the front reception area by the stairs, hostages started to tumble down, thrown from man to man until they reached me. Ginge and I became an integral part of the chain and proceeded to launch hostage after hostage towards the door and the waiting reception party.

'Watch out, he's a terrorist!' shouted one of the men on the stairs. I looked across to where the shout had come from. One of the assault team hit the man with the butt of his weapon and launched him down to where the stairs cornered sharply to the right. He stumbled around the comer and down the last few steps. It was Faisal, and he held a grenade in his right hand. Without hesitation I fired one short burst of four rounds at his chest. All four of the team in the foyer also opened fire. Faisal slumped to the floor with twenty-seven holes in him. He didn't spasm or spurt blood everywhere. He simply crumpled up like a bundle of rags and died. More hostages were on their way down now, arriving thick and fast. The gunfire had subsided. One of the officers from the team upstairs came down shouting at all and sundry, 'Get out, get out, the buildings on fire.' He sounded a bit worked up, so I grabbed him by the arm and shouted, 'You get fucking out. I've got to make sure everyone else in front of me is out first.' He looked at me for a second and then, realizing the sense in what I'd said, went out the back door.

Now I saw the soldier who had messed up his abseiling come down. His eyes were glazed and one of his legs was terribly burned. He must have been in great pain, but he refused to let anyone help him. At least he was down safe -he had the two men on the roof to thank for that.

As the flames crackled around us, the different sections of the team started to report in. Their areas were clear, and their soldiers were out. Ginge and I pulled back and went to help with the prisoners.

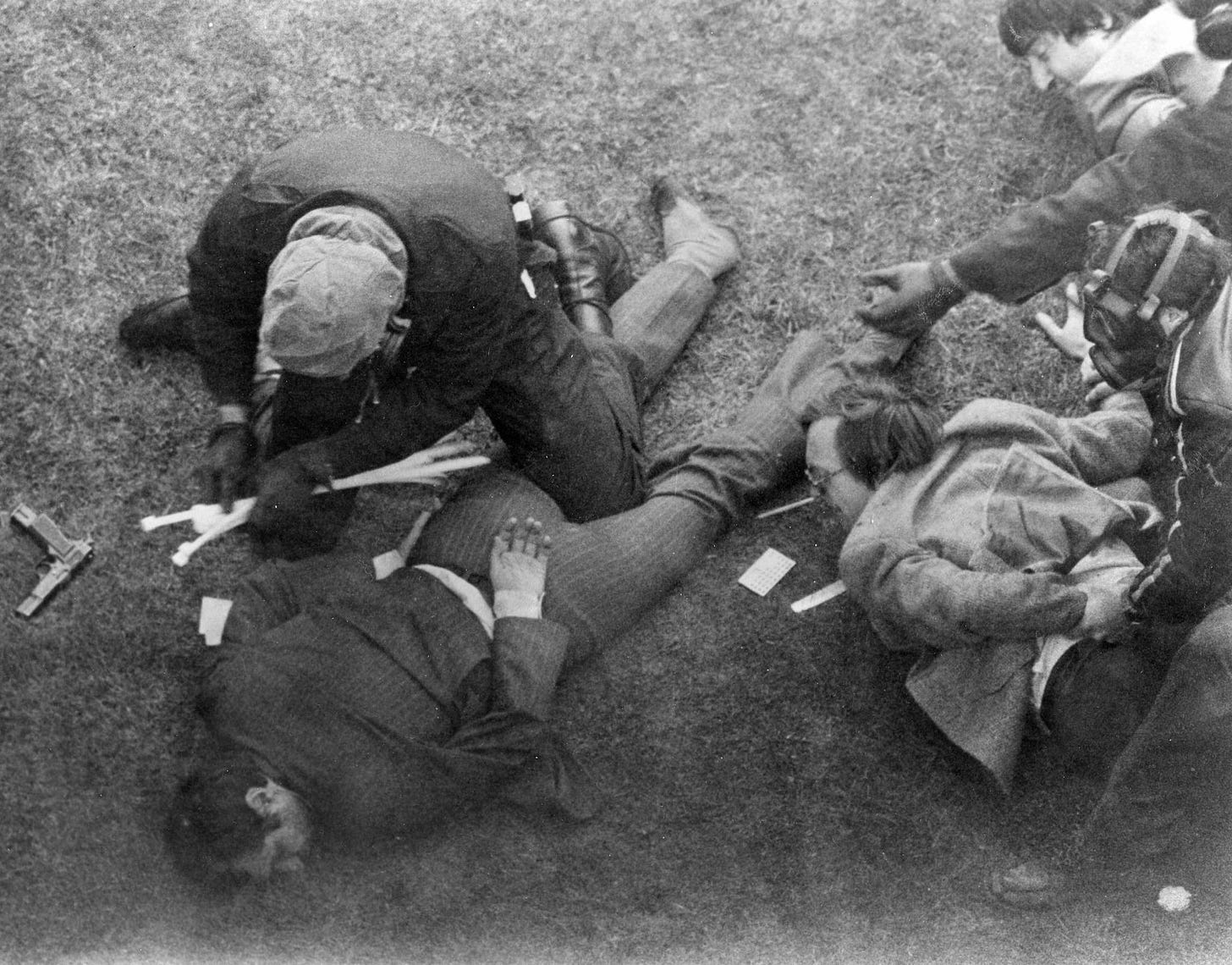

Outside on the lawn, the hostages were laid face down with their wrists handcuffed behind their backs. They would not be released until they were all identified and calm. Sim Harris was twisting to one side and looking at one of the handcuffed men. 'He's a terrorist!' he shouted. Big Tony, one of the reception parties, pulled the man in question to his feet and began to walk him away from the group. At first, I thought he was going to lay him down a short distance away, but he continued walking, towards the rear door of the flaming building. I ran over with Ivan, a new member of 9 Troop, and made sure that Big Tony laid the man down on the ground where the police could see him. We never knew for sure what Big Tony had in mind.

While the police and their dogs surrounded the prisoners and began to take over, we were ordered over the radio to return to the Royal College of Surgeons. As I walked through the back door I was assaulted once again, only this time by policemen. Their huge hands slammed down on my back and words of admiration flowed freely. 'Well done, lads, brilliant.' I was bowled forward into Stevie from 7 Troop. He stopped and turned to the worshipping throng. Pausing theatrically, he pulled up his gas mask, exposing his swarthy features, and smiled. The policemen fell silent, waiting for the heroic pearls of wisdom about to issue from this conqueror's lips. 'Who won the snooker?' he asked.

Our Job was done. All we had to do now was go home to Hereford. We had suffered only two casualties: the man on the rope, who had severe bums to his legs, and Gwyn, who had shot the end of his own left index finger off. He had been using a shortened version of the MP-5, the MP-5 Kurtz, and in the excitement, he allowed his finger to wander over the front of the barrel as he fired.

As we reorganized, we had to hand over any weapons that had been fired to the police so they could be checked by forensics and then matched to our stories at the inquest. As we handed them in, we had to state how many rounds we had fired. 'Twelve rounds,' said the man in front of me. 'Four rounds,' I said. The next two men in the line were old veterans of many campaigns, the elite. 'Three magazines each: they informed the policeman. I looked back, astounded. How could they justify firing that much ammunition? They had been tasked to clear the basement area; there had been no terrorists in that zone. I hadn't been there, but all my training had taught me to fire only when I was presented with a clear target. These two men had been room-clearing as though in a war zone. Thank heavens they hadn't been upstairs.

William Whitelaw arrived, and we were all called into the lobby of the college to hear what he had to say. He had tears of emotion in his eyes as he spoke. 'I always knew that you would do a good job: he said, 'but I never knew it would be this good.' He wanted us all to go out front, to be paraded in front of the world's press -to be famous for a day and have our pictures taken. Hector soon put a stop to that idea, and we packed ourselves into the back of police vans and the pantechnicon and disappeared back to Regent's Park Barracks, where our own vehicles were parked.

Shortly after we arrived, Margaret Thatcher turned up to see her 'boys', as she called us. We lined up and were introduced to the PM one at a time. As my turn approached, I was truly excited at the prospect of meeting her. She extended her hand, which was immediately crushed in my over-enthusiastic grip. Demonstrating years of practice, she allowed her hand to go limp in my grasp. She was small, much smaller than I had imagined, and her make-up looked like it was cracking from her skin in layers. Perhaps it was that way for the cameras she had been facing outside Downing Street. The older guys weren't fazed by her at all. 'When are we going to get a pay rise?' some of them asked.

The news came on, and we moved over to a TV in the corner of the room which had been brought in specially. There was no other furniture, so we sat down on the floor to watch the assault. Maggie Thatcher sat down with us and joined in the cheering as we watched ourselves in action.

It had been quite a day, but now it really was over and all we wanted to do was get home. Without much thought, we bundled everything into the back of our Transit van and, with Tom driving, left London, heading out towards the M4. As we passed through Chiswick, one of the back wheels of the van clipped the sidewalk and we ended up at Heston services to repair a puncture. We managed to get the spare wheel ready but then realized that the tools were hidden beneath all the unused weapons still in our possession. If we took them out, the weapons and ammunition would be in full public view, even though it was dark. As we were trying to work out what to do, I saw an AA van parked about fifty yards away. 'I know, I'll get the AA to change it,' I said. Before anyone could protest, I strolled over and asked the AA driver if he had heard about what had happened in London that day. He said that he had, becoming quite animated about events. 'Well, I'm one of the blokes who did it,' I told him, ‘And I have a problem.'

I explained our predicament to him and, not sure whether to believe me or not, he drove over to look, as much out of curiosity as anything else. Confronted by four tired-looking heavies, and with the signal from a police radio bleeping in the front of the vehicle, he was convinced and changed the wheel for us. The AA can take some credit for their involvement that day -and we weren't even members.

It took another three hours to get to Hereford, with a stop at Greasy Joe’s Cafe in Cirencester en-route. Without the weapons that the police had confiscated, the team was effectively out of commission for a couple of days, so we unloaded what we could and cleaned up. By the time we had finished it was about three in the morning; we were told to report in after lunch the following day. I went home and climbed into bed with Heather.

The following morning Heather and I were sitting with Derek from 8 Troop and his wife in The Golden Egg Cafe. The siege was on everyone's lips. Behind us a group of people were saying how they would love to meet the men who had carried out the mission. Derek and I smiled, while our partners almost hugged themselves, basking in their secret knowledge.

True to tradition, a piss-up was organized almost immediately. No wives or girlfriends was the order of the day - not a decision I was really enamoured of, but some men's wives are better company than others I suppose. Gifts flowed in from all over the country: cases of whisky from breweries, Cup Final tickets from football clubs, Derby Day tickets, and so on, the list was endless. The squadron itself got to see a few bottles of champagne at the piss-up; the rest disappeared to destinations unknown.

I felt withdrawn at the party: drink alone wasn't enough to get me in the mood. Trevor Lock was there with his wife, and it was a pleasure to meet him properly and to know that I had played a part in saving his life.

Before the siege very few people had heard of the SAS. Now the whole world wanted to know us. Instead of getting straight back to training, as we should have, we were turned into a performing circus, demonstrating our techniques to any interested member of the royal family and their corgis. Our standards dropped appallingly until the next squadron took over; then we could rest on our laurels no longer…

Robin Horsfall books are available from Amazon at https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?k=robin+horsfall+books

Signed copies of Robin’s books and A4 photographs from operation Nimrod, are also available at www.robinhorsfall.com/shop